Lots of people are angry at Simone Biles. This pisses me off.

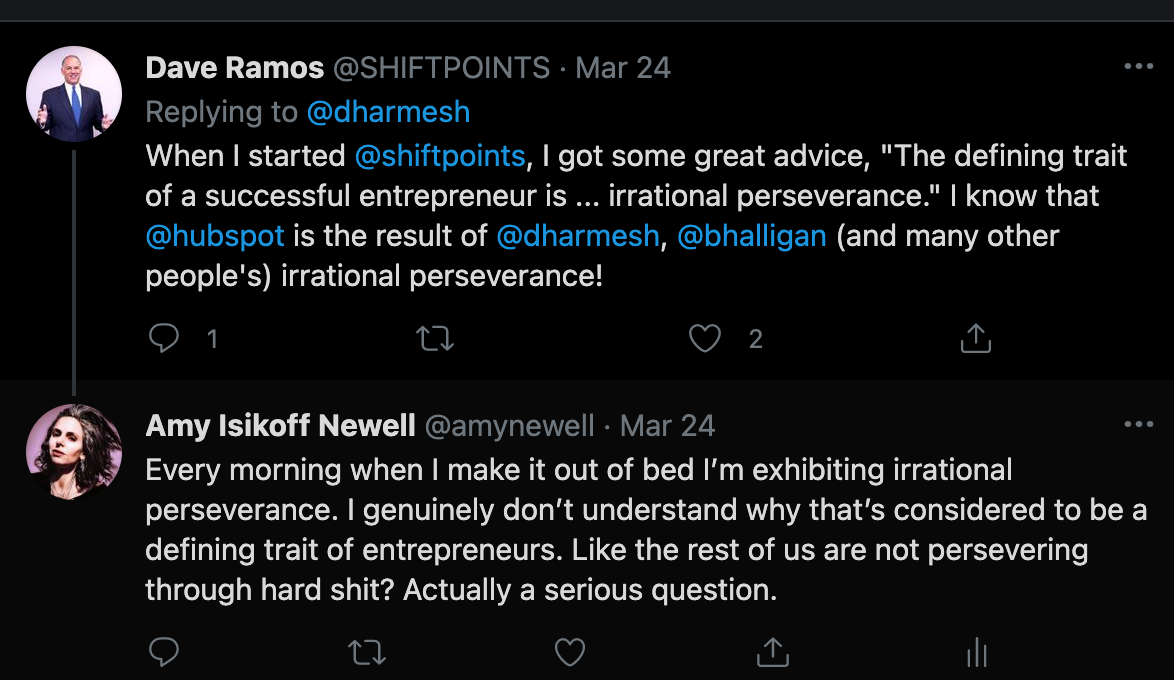

Because of this whole thing I remembered this acid and yet serious response I gave to this entrepreneur bullshit ra-ra crap I saw on Twitter a few months ago.

Sadly the dude did not answer me to explain why successful entrepreneurs are different in kind than people who have to commute 3 hours each way to clean Facebook’s offices, or different in kind than people who walk from Guatemala to Texas carrying their babies in their arms trying to keep from being murdered by gangs. No one else exhibits the kind of grit successful entrepreneurs exhibit?

Now might be a great time to introduce you to the Twitter account VCs Congratulating Themselves.

*

Why did I say I was exhibiting irrational perseverance by getting out of bed in the morning?

Well, some mornings I wake up to what can only be described as a long, continuous screaming sensation in my head. Sometimes when I get out of bed despite this screaming sound I sink right back down on the floor and turn to contemplating the relief I might obtain from the screaming sound by, say, stabbing an ice pick right into my forehead. On most of these days, in the before-times, I nevertheless picked myself up from the floor, popped a little pink 25mg Seroquel to take the edge off, and crossed the river to go in to work, where I often attended meetings all day long, in between which I would cry in the stairwell, sometimes arriving to my next meeting still wiping the tears from my face.

Okay, actually some meetings I just cried straight on through. “Don’t mind all this,” I’d say to people, gesturing at my teary face, “it’s not relevant.”

*

I’m an unbelievably privileged human being, but I do suffer, and I do, generally, soldier on. The idea that soldiering on is a specific trait of successful entrepreneurs is, bluntly, obscene. It represents an absolute failure to consider the perspectives of other human beings who find themselves in different circumstances, along with the willfully ignorant capacity to truly believe that you have succeeded (or will succeed) because you are better than other people, because you have more of some magical trait. Call it grit, strength, perseverance, courage. Believe that it has nothing to do with your life circumstances, and that it means you deserve everything you have in life.

*

Let us now take the case of Simone Biles. Many things have already been said, many of them deeply, inhumanely, stupidly wrong. This is a good thing to read, because it explains precisely what Ms. Biles has already persevered through and the risk to which she was exposing herself and her team if she continued to compete when she knew her head wasn’t in it.

In order to illustrate how difficult and impressive the thing she did was, I want to share some of my own experiences, stemming from my own struggles with mental illness.

I want to talk about times I’ve had to pull out of things because of my mental state, and about all the times I maybe should have but didn’t, because I didn’t want to be perceived as unreliable, because I expected that I would be judged harshly for it, that it would hurt me, that I would be letting people down. And because I drew my own sense of self-worth from rolling right on through the pain.

*

In July 2012, a very bad month in a very bad year for me, I was waiting for a bed to open up at McLean, a very famous mental hospital near me. I had asked to go inpatient because I thought I might die if I did not find a way to feel better. While I was waiting for the bed to open up, I continued to go to work, where I was in the middle of a 2-week sprint serving as scrummaster on my engineering team. I went to work each day with a packed bag in the car. The day I got the call that I had a bed, I turned to my manager and the other scrummaster and said “that’s it, I’m going, the sprint is all yours now.”

I gave that responsibility up at the very last second I could, and it hurt.

*

In September that year I started a course of electroconvulsive therapy. During the month that I was receiving treatments 3 days a week, I did not work. But when I went down to 1 day a week, I started going back into work on the days I didn’t get a treatment, and sometimes if the treatment was in the morning, I would go to work in the afternoon.

Later that year a close friend committed suicide while I was texting him. I still went to work.

A few weeks after that, my doctors told me I should check into the psych ward immediately because I was manic and I said I had some things to do first, I had to finish out the sprint and teach a class.

*

In the spring of 2017 I worked through a three month depressive episode so terrible that I emailed myself every day about how much I wanted to be dead. I was leading a software migration project at the time. I kept right on doing so, while getting myself on a long waitlist for ketamine infusions, a then-novel treatment for the severely depressed.

In June, as the project was coming to an end, I finally got off the waitlist for infusions. The day of my first infusion I went to work until noon, as that was the day we were finishing migrating the system. Then I went to get my infusion. After my infusion, still reeling from its effects, I logged onto Slack to see how things were going.

I got infusions three days a week for two weeks and I worked in the mornings before them and on the days in between them, and sometimes after them too.

*

I worked full-time through what we still somehow refer to as “The Pandemic” in past tense, although we can all see now that there is not yet and maybe never will be a past tense. I was also effectively running a 24/7 teen crisis center at my home and, of course, dealing with my own mental illness.

I have written already about how hard it has been to come to rest from all that.

I am still so utterly exhausted it feels as if I will never put myself back together again. I know that I will, because I always do, but I don’t feel like it. Like so many people, particularly mothers, I feel that I have been broken.

*

Here’s a poem I wrote about working while also trying not to die. It was originally published in Room Magazine:

High-functioning And now I have found myself a little delusional again Weeping, dosing myself with Seroquel like some racehorse Bound tomorrow for the tracks. From far away I am Watching this out-of-control process, this database-locking Transaction, this overwhelming certainty that I am in brute About to die. And the other side of it, just as distressing, The word madness ringing through my head like bells Toll when the king is dead. All my kingly life on the chopping Block, whoever you choose to believe. The effect is paralytic. But I have no time for this. By morning I must be up, across The river, for another day of decisions and miracles. And Whatever I have told you about myself and my crazy I Must not let my mind bring its arguments to you, my Colleague. I cannot afford for you to file me under Unreliable. I have too much I want to get done in this place.

*

I rolled on right through all that pain, all that accumulated trauma, for years. I rolled on because I thought if I stopped I’d never start again, because I thought if I couldn’t earn money I was worthless, because I wanted to prove that I wasn’t damaged goods.1

I have been meaning to write a memoir about my experience with mental illness for a while now. The original title was “I Can Do Anything Sane People Can Do, Only Dressed More Fabulously.” It was going to be all about how I refused to give my mental illness any quarter, how I just kept rolling on. Unstoppable. Invincible, Incredible Amy, look at her go.

A friend once described me as the superhero who every day lands a burning plane and then walks away unscathed, tossing my scarf behind me as I go. “Clear the runway boys, we’re landing on a wing and this bitch’s impudent refusal to succumb unless she can be the last one out.” It does feel all the time like I am flying a plane that is on fire. And I did take pride in making it look easy, that landing.

Another quote: “You are like Inigo Montoya, slumped against a wall, still parrying effortlessly.”

How I cling to that, for dear life, like I’m clinging to a cliff face in a rainstorm.

Every time I have had to let that go it has felt like falling to my death.

*

I can’t speak to what Simone Biles has going on in her head. It’s not my fucking business. What I can say is if your job requires you to throw yourself very high up in the air and do a bunch of flips and then land upright while millions of people are watching, it makes good sense to take some time off from doing that job if your plane is on fire and you’re not real sure you can land it. Simone Biles doesn’t owe it to anyone to try to land that burning plane when she knows she should not.

*

I have, at times, described my life as "free-climbing El Capitan in a rainstorm.”

Imagine me halfway up a cliff face, grabbing onto the tiniest of handholds, in heavy rain. Imagine feeling like that every day. Imagine not knowing how long that feeling will last — days, or weeks, or months. Imagine knowing (but not feeling) that while yes, it is temporary, it will leave, that it will also always, always come again.

There’s no cure.

*

In November 2016 I was supposed to go to Buffalo to give a talk, ironically, it turned out, about my experience with bipolar disorder for the organization Prompt, a non-profit focused on mental illness in tech.2 It was my first public speaking engagement. I had been asked to speak and I had said yes and I had bought the plane tickets and I had made the hotel reservations.

I was, of course, terrified.

I was also very sick, as I often am in November. I was very, very depressed, not a quiet sad slow kind of depressed but excruciating pain combined with sheer terror combined with absolute despair, with a delusional edge. Not straight up delusions, but I could see that I was fixated on terrible things I had done and terrible things that would come to pass that were, perhaps, not exactly what was happening. When I talk about the apocalyptic flavor of my mental illness, this is what I mean: the sense that I have done terrible things, am a terrible person, and I will be punished for it, that I have destroyed my life.

What people sometimes do not understand about this flavor of depression is that there is a vast and lonely distance between what you might believe to be true (“I will get better”), and the ongoing, visceral experience that feels like the only truth left in the world, the feeling that this time we have finally reached the very end of the road.3

This is why I say to you that I know a thing or two about Apocalypse.

*

The week before I was supposed to go to Buffalo, Trump won the election. My despair and terror escalated. One day that week I was sitting in the bath and I heard a sound like everyone in town had gone outside and begun to scream all at once. I jumped out of the bathtub and rushed to the window, expecting — I wasn’t sure what — missiles overhead, bombs raining down, military marching down the street, and at the very least, all the screaming people I had heard.

I saw nothing. Everything looked completely ordinary. I texted my babysitter in fear, were the kids okay? Yes, she wrote back, puzzled. We’re at the playground.

It was hours later that I realized there hadn’t been any screaming at all, that my mind had actually made that up, that I had had a hallucination.

The screaming was in my head.

At the time I didn’t realize I ever hallucinated, and maybe I hadn’t much before. I later grew to recognize myself as someone who often has very minor hallucinations, not scary ones, but just…a slightly altered state of consciousness akin to the tiniest of psychedelic trips. And then once in a while something very scary, like the actual end of the world.

I thought about checking into McLean again, if I could get a bed. I talked to my psychopharmacologist. “I’m supposed to go to Buffalo,” I said. He asked “Do you know anyone in Buffalo?” I did not. I could barely leave my bed and flying is hard for me even at the best of times. I had no one to come with me to take care of me, and losing my mind even further alone in a strange city was a bad bet. He said I should cancel. For once I actually listened to his advice.

I told the organizer I couldn’t come, but maybe I could deliver my talk remotely. I started asking AV friends if they had good equipment for this. I continued to contemplate hospitalization. And I fixated, of course, on what a failure I was if I didn’t somehow show up to give the talk, even though I still really couldn’t leave my bed, or do anything for anyone, or eat, or sleep.

I was wracked with pain all day long and lost in self-hatred over my failure to deliver on something I had promised to do.

I tried to execute on that talk right up until a couple of hours before I was scheduled to give it, from bed, over Skype. I watched the boarding time for my plane flight come and go.

That flight to Buffalo (and the one back) remain the only flights I have ever missed. I don’t miss flights.

I watched the time I was supposed to speak come and go too.

I lay in bed contemplating the apocalypse I was experiencing, the one where I became permanently unreliable. “I can do this,” I thought. “I can usually do this.”

I couldn’t do it.

*

I am 46 years old and I still carry around the shame of every single time I failed to execute on something I’d said I would do, regardless of how sick I was when the time came to do it.

It takes unbelievable courage to say “no, I can’t do this.” The bigger the commitment, the more people who are counting on you, the more courage it takes.

I have to learn over and over how to say no I can’t do this right now, it’s not safe for me, it’s not healthy, it’s not good for anyone, I have to pause, I have to rest. I am still not very good at it. My inclination is just to keep going until I am forced to a stop, by my body or by other people, and when that happens it always feels like a betrayal, and I’m angry about it.

It’s much better when I insist on stopping myself, but it still hurts, every time. It chips away at that superhuman image I’ve cultivated, the one where I’m always parrying effortlessly, always landing that burning plane.

I never believe I’ll be given any grace for being sick. Even though I have been given that grace, by many people in my life, many times. Over and over again. I will give someone else that grace, explain why, even, say I have been given this grace and now I can give it to you, take it, it’s here for you, the acceptance of your humanity. I can say that and still, when I need the grace again, be sure I will not get it, that I do not deserve it.

It pleases me to see Simone Biles being able to begin to believe that she is not simply how many flips she can do in the air on behalf of her country.

*

Here’s your Taylor Swift for the day: “It’s time to go”, a bonus track on the deluxe edition of Evermore.

*

Those people who call Simone Biles weak — they have no fucking idea. At the age of 40-something I could barely bring myself to bail out of giving a short talk at a small technical conference, even under doctor’s orders. Finding the courage for that was unbelievably difficult (which is why I did it so slowly and so messily, which I regret). At 24 there was absolutely no chance that I could have made that kind of choice and clearly stated the reason why. I cannot imagine what courage it takes to step back from the ACTUAL OLYMPICS, but I know it’s a LOT.

If you don’t think that takes incredible strength and unbelievable grit, you don’t have any idea what those things even are.

On the other hand, maybe you know exactly how much strength that takes, and it scares the shit out of you, and that is why you call it weak.

There’s a great book on this topic, Laziness Does Not Exist.

Prompt has since merged with Open Sourcing Mental Illness, for which I continue to be on the speakers’ bureau.

I like the Beck Depression Inventory, a popular measure of depression, self-reported by the individual experiencing the depression. I like it because it does a good job of capturing the paranoid edges of depression in a way other measures of depression just don’t. “I blame myself for everything bad that happens.” “I expect to be punished.” “I am so worried about my physical problems that I cannot think of anything else.” “I feel I am a complete failure as a person.”. When you’re feeling okay and, I guess, if you do not believe in hell, the idea that you are bound for punishment seems…odd. When you are very, very depressed, it seems obvious.

The game of GRIT is a weird problem, it is known that it does not universally work https://freddiedeboer.substack.com/p/grit-or-the-moralists-fable-about-education

Because mental "illness", like intelligence, is genetically adaptive for Socio-Economic Status AKA Class https://astralcodexten.substack.com/p/non-cognitive-skills-for-educational

And they influence reproductive success, and one can assume by extension dating and friendship success https://wyclif.substack.com/p/the-natural-selection-paper-part-908

Then again, the question is not "who is really weak", but rather "what occupation requires which personality traits" and businessmen is a clear unique breed.